Coverage – the story of Julius Caesar told through the modern media

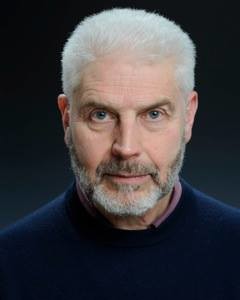

Posted by Ian Grant | Uncategorized | No CommentsAshley Pearson’s Coverage opens at the Courtyard Theatre in London this evening. It’s a modern take on the story of Julius Caesar as told through the lens of a right wing US 24hr news station. We spoke to Al exander Grant, who plays Julius Caesar in the production.

exander Grant, who plays Julius Caesar in the production.

Coverage introduces a sense of modern day 24/7 news reporting to Julius Caesar… what is the balance between the original material and this modern interpretation?

“It’s a completely contemporary rendering of teamwork that falls apart because of human ambition and frailty,” said Grant. “Ashley Pearson’s script lands us in the bustle of a TV newsroom, broadcasting live news of contemporary political events in a Roman/American republic. The shifting relationships of the news team mirror the crumbling allegiances of the Roman senators as they plot to murder a political leader who reaches beyond the republican ideal of the equality of every citizen. The senators speak the Shakespeare text, intercut with the Aaron Sorkin-like dialogue of the newsroom.”

Please give us a brief introduction to your role…

“I play Julius Caesar. In Coverage, Caesar is a liberal-minded presidential candidate, reaching for sole leadership of the state. He believes in gun control and the individual responsibility of citizens to run their own lives. But he also believes utterly that his own powers of leadership overtop all others.”

Are people today blind to the influence of the media and in particular its right wing bias?

“No. People select the news they watch, hear and read and react to it in a manner of their own choosing. Fewer people choose centre-left channels than centre-right and beyond. There is a greater volume of noise and further reach in the right-wing channels. In the UK the BBC largely holds the ring. In the US, money talks even more loudly, so the right-wing volume is very high.”

Can we draw parallels between the Roman Empire and modern day America?

“Only with a broad brush. The Roman Republic was very different from the American republic that has emerged from the 18th-century Enlightenment and the movement to votes for all in the 20th-century. But Rome was built on the management of a very stratified society, with slaves at its base; military might; and, from the fourth century AD, a Roman emperor keen on imposing an evangelical Christianity across his empire. Like all empires – the Chinese, the British, the Islamic – there are fundamental similarities which reflect the fact that people don’t change much.”

In a world of non-stop media, does theatre have a stronger role than ever to play in connecting art with audiences in ‘real life’?

“Theatre is wonderful for that. At its best moments, the human life and fire that is created by actors is reflected back in a response ‘in the moment’ from the audience. This forms a connection between people of such openness that is unbeatable in any other medium.

Coverage runs at the courtyard Theatre on Tuesday 26th January – Sunday 31st January. For more information visit: http://www.thecourtyard.org.uk/whatson/654/coverage.

Recent Comments